Fernando has mentally prepared to never see his children again twice in his life. The first was during a home-invasion-turned-kidnapping he didn’t expect to survive, when he prayed that his children would remain in the basement, watching a movie, until the robbers left. The next was when he was sitting in an immigration detention center, expecting to get deported.

“Yo estaba en el 99.9 chance de deportación, y yo le dije a mi esposa, ‘se feliz, busca otra persona.’ No quiero que este sola. A mis hijos, prácticamente me despedí de ellos, estaba resignado a no volverlos a ver.”

“I was 99.9 percent sure I would be deported,” Fernando said. “So I told my wife, ‘be happy, find someone else.’ I didn’t want her to be alone. My kids, I practically said goodbye to them, I was resigned to never see them again.”

The home invasion left him traumatized, but able to apply for a U-Visa, a type of visa that provides a path towards citizenship to survivors of certain crimes. The processing time for the U-Visa dragged on: a year, then two, then three years went by, and then, in one awful year, Fernando’s father, brother, and a beloved aunt all passed away within months of each other. Fernando, who had been living in the United States for 20 years, and awaiting his visa for another three, still couldn’t go home to see his family.

“En esos días, no me importaba. Yo solo quería ver mi familia, pero mi mama me hizo ver la realidad: ‘vas a venir, bueno, y ¿cómo vas a regresar?’”

“In those days, I didn’t care,” Fernando said. “I only wanted to see my family, but my mom made me see reality: ‘You’ll come, fine. How are you going to get back?’”

In the haze of grief and trauma from so many losses in a row, Fernando became addicted to drugs. He was caught with a small amount, and served three months in jail. When he was let out, a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement officer was waiting.

The next year of Fernando’s life, four times as long as his actual jail sentence, was spent in immigration detention.

“Lo más duro fue la separación, algo que no se lo deseo a nadie. Mi niño tiene autismo, y cuando hablaba por teléfono y me preguntaba dónde estaba, yo le decía ‘estoy trabajando mijo,’ y el me preguntaba, ‘¿cuándo regresas?’ ‘Ya mero, tu eres el hombre de la casa, cuida a la familia.’”

“The hardest thing was the separation, something I wouldn’t wish on anyone,” Fernando said. “My son has autism, and when I would talk to him on the phone, he’d ask where I was and I’d say, ‘I’m working, son, and he’d ask ‘when will you be back?’ ‘Almost, almost, but you’re the man of the house now, you have to take care of the family.’"

Before he was imprisoned, Fernando had been his family’s main breadwinner, but now, an old back injury meant his wife could only work a small number of hours a week, barely enough to keep the family afloat. The lack of financial resources, compounded with the poor treatment inside the detention center, meant that without a commissary fund, Fernando often went hungry because of a lack of adequate food.

“Pase mucha hambre porque mi esposa no tenía dinero para mandarme. Decidí trabajar en la cocina, y eso me ayudo mucho. No tenía para hablar a la casa, todo el dinero que me pagaban, lo poquito, lo juntaba y el fin de semana hablaba, 5 o 10 minutos, y entonces otra vez hasta la próxima semana.”

“I suffered a great deal of hunger,” Fernando said. “I decided to work in the kitchen, and that helped me a great deal. I didn’t have enough money to call home, so all the money that they paid me, the little bit, I would gather it up and during the weekend, I would call for some 5 or 10 minutes, and then again wait until the next weekend.”

For Fernando, however, what was the most difficult was the emotional aspect of incarceration.

“Duele más el maltrato mental que el maltrato físico. Te denigra como persona, y es hasta un grado que dejas de creer hasta en ti mismo… Lo que si se me hacía bien triste es que te recuerden quien eres para ellos. Tu podías decir, yo soy fulano, pero no es cierto, eras un número nada más.”

“The mental mistreatment hurts more than the physical mistreatment,” Fernando said. “It denigrates you as a person, and it’s to a degree that you even stop believing in yourself. … What made me really sad is for them to remind you of who you are to them. You could say ‘I’m so and so,’ but it’s not true, you’re just a number.”

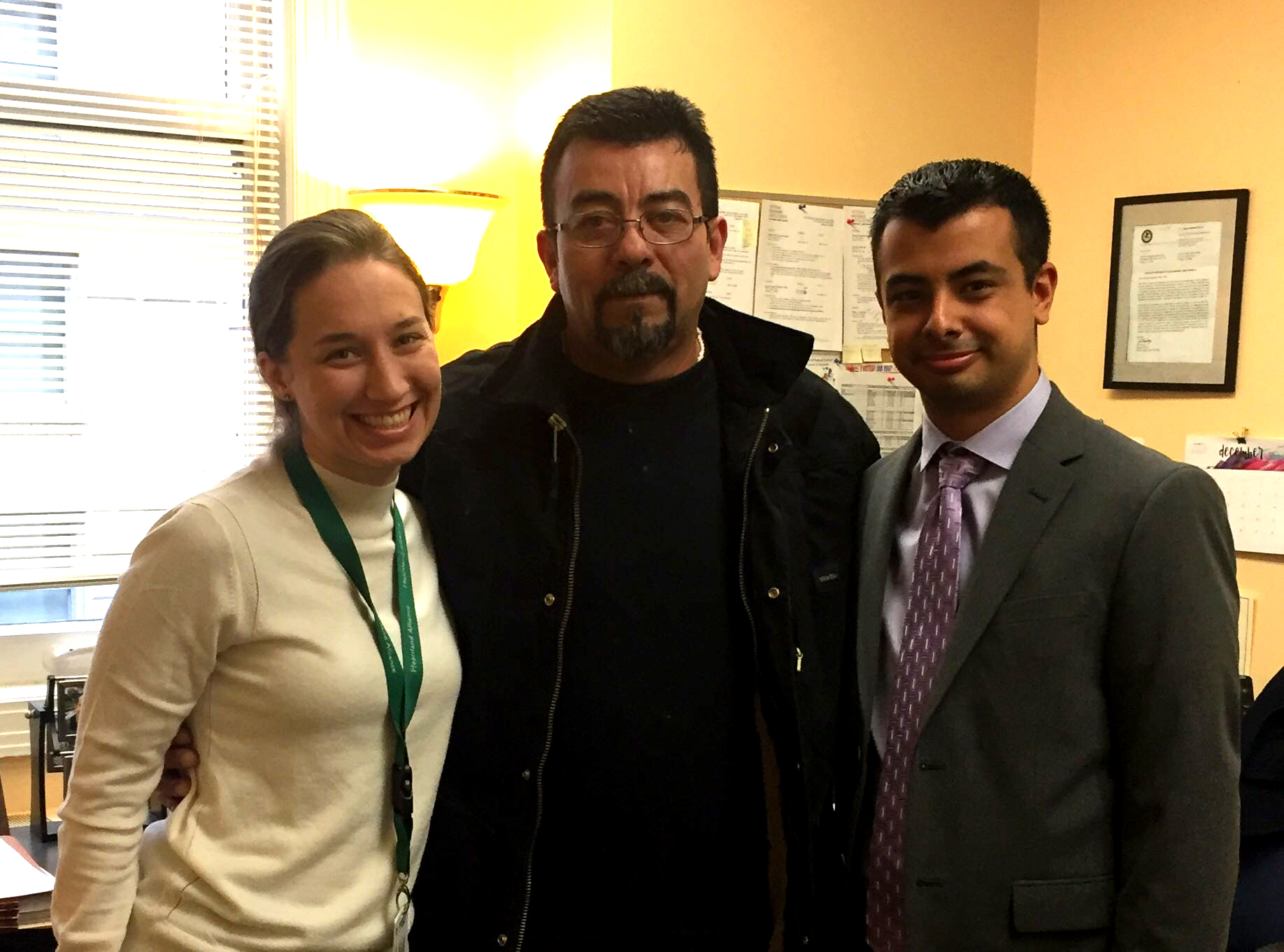

Through the National Immigrant Justice Center’s detention project, Fernando was given legal assistance by attorney Hannah Cartwright and Jesse Johnson, an accredited representative. They fought for his release from detention and secured his family’s U Visas. Today, Fernando is struggling to find a job in his field of construction and floor laying, and is making ends meet with cleaning jobs, which don’t pay as well. Even though Fernando has now been out of detention for a little less than a year, the experience is still with him.

“Siempre decía, cuando salga lo voy a dejar atrás. Siempre decía hay un mejor mañana, pero la verdad es que eso no es cierto, todavía aun que tengo documentos, estoy pensando, ¿qué va a pasar mañana? ¿me van a parar? ¿me los van a quitar? No se.

“Cuando sale uno, uno se trae al encierro por dentro, todos los recuerdos. Uno se dice, lo voy a olvidar, y no es cierto, no se olvida, es estresante tener que vivir con temor todo el tiempo.”

“I would always say ‘when I get out of here, I’m going to leave it all behind,’ Fernando said. “I would always say ‘there’s a better tomorrow,’ but the truth is that that just isn’t accurate. Even now that I have documents, I’m always thinking, ‘what’s going to happen tomorrow? Are they going to stop me? Are they going to take my papers away?’ I don’t know.

“When you get out, you bring the lockup with you, all the memories. You say ‘I’m going to forget it,’ but it’s not true, you don’t forget. It’s stressful to have to live with fear all the time.”

Alejandra Oliva is a communications coordinator at NIJC